Crocus gatherer, mural painting, Xeste 3, Akrotiri (Thera), 15th century BCE, National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Perfumes, sounds, and colors correspond. Charles Baudelaire, Correspondances

Phaon was an old, ugly sailor who made his living ferrying passengers from the island of Lesbos to Asia Minor. One day, he unknowingly carried Aphrodite, who did not reveal her identity to him. When Phaon refused payment for her passage, she gave him a scented ointment to thank him instead. When he applied it, he became so young and beautiful, that every woman who saw him fell in love with him, including Sappho, who killed herself after he shunned her. Already in Antiquity, perfume was considered a powerful means of seduction.

Corinthian aryballos with a frieze of warriors, 6th century BCE, Musée du Parfum Fragonard, Paris.

The scents that captivated the Ancient Greeks have long since dissipated, but we have many sources that allow us to sketch out a history of perfume in Antiquity. Theophrastus was a philosopher and botanist who lived in the 4th century BCE. In his Treatise On Odors, he describes age-old rituals, especially the use of incense for funerals, as well as practices for the living to take care of their bodies. As heirs to Ancient Egyptian science, the Greeks had developed distillation techniques to create essences for their favorite scents, such as laurel, marjoram, iris, and cardamom. Theophrastus also provides the modern reader with a certain amount of vocabulary, the variety of which attests to the development of the art of perfumery in Ancient Greece. Perfume manufacturing combined a ground aromatic essence that was soaked in water or wine along with an excipient, usually a plant-based oil. These materials were combined either by soaking them at ambient temperature or by heating them in a double boiler. Resin or rubber was used as a fixative. Another work essential to our knowledge of ancient perfumes is De materia medica by Dioscorides, a Greek physician who lived in the 1st century CE. He reiterated much of Theophrastus’ writings, and he developed some of the recipes such as the rose oil formula in Vol. I of De materia medica that Theophrastus had described in Vol. XXV of his Treatise On Odors, and which his contemporary Pliny the Elder also mentioned in Vol. XIII of his Natural History. This recipe uses rose as an aromatic essence, oil from green olives, almonds, sesame, or moringa as an excipient, honey, wine, or salt as fixatives, and orcanet or cinnabar for coloring. He gave us some of the secrets to the mythical scent of Aphrodite’s rose, which was, according to legend, made in her palace in Cyprus, as well as the most fashionable perfume of the time in Ancient Rome, when the verses of Virgil’s Eclogues infused the culture of the early Roman Empire. The paintings of cupids making perfume at Herculaneum and Pompeii allied love and perfume in a tradition that was already age-old.

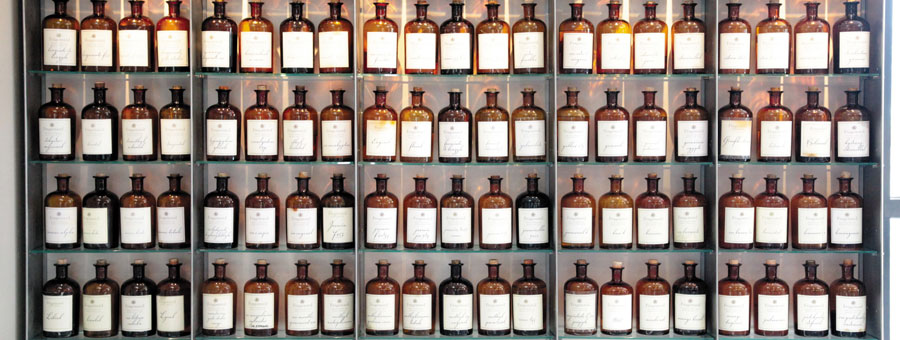

Archaeology is another essential source that has reveal a lot about the place occupied by perfume from the origins of civilization to Ancient Greece. Tablets in Linear B from the 12th century BCE unearthed at the Palace of Pylos (and now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens) list various accounts that mention coriander to be used for perfume, as well as the significance of the saffron trade. From this same pre-Hellenic era, frescoes on Santorini depict women collecting crocuses and saffron (image 1). These images from the second millennium BCE of the harvesting of flowers in part for cosmetics purposes were followed by the widespread use in Archaic Greece of vases to condition perfumed oils. During the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, Corinth exported thousands, if not millions, of small, globular vases called aryballos across the Mediterranean, which were filled with perfumed oils (image 2). In the classical era, certain perfume vases were made in shapes that appeared to evoke the products used to make their contents, such as the miniature amphorae used to hold almond oil. And in a return to the Asian and Egyptian origins of perfume, bottles of millefiori molded glass (a technique imported from the Orient) were widely distributed by the Greeks, starting in the 5th century BCE. The luxury of these containers, which were at times even made out of rock crystal or precious metals, corresponded to the refinement of their perfumed contents.

All these vases remain largely silent about what they once held, though. Even if scientific research fills some of this void, the perfumes, sounds, and colors no longer correspond… But the legend of the erotic power of Greek perfumes remains, such as the one that Hera wore to win back her husband against the backdrop of the Trojan War (Iliad, Song xiv): “First she uses ambrosia to purify her desirable body. Then she takes a pleasing, divine oil, perfumed to her tastes. When this oil is dispersed on the bronze threshold of the Palace of Zeus, its scent spreads across the sky and the earth. She rubs it on her beautiful body… Zeus smells it and love captures his prudent heart, a love as strong as that of yore.”

By Isabelle Bardiès, conservateur en chef au musée de Cluny à Paris